The Bush Chicken presents a translated radio lecture delivered on January 22, 1933, by amateur anthropologist and photographer, Paul Julien. The broadcast occurred after a 1932 meeting of Chief Suakoko in Liberia. The radio transcript grammar has been edited for clarity from the original source.

In the center of the black republic [Liberia] lies the village Suakoko. The area is rather busy because the big forest path that ranges from Kakata, in the south, to the north-east passes it. Suakoko is a big village. I counted about 200 small huts, cylindrical structures with cone-shaped grass-thatched roofs.

It was late in the afternoon when we arrived and despite the hour, the village was full of life and activities.

I was given a small square clay building, within the government compound by the chief to spend the night. Nearby, women were pounding cassava, in exactly the same way rice is pounded in our Indonesia. From further down in the village, the flapping of a weaving loom operated by a Kpelle weaver sounded.

A young man in wide Mandingo dress suddenly appeared in the doorway of my hut. His clothes, though from inland weave, were well taken care of, and the man was even wearing sandals from a Sudan make, which is rare in the interior.

Everything pointed in the direction of this man being a “Negro†from an upper-class background. He was followed by half a dozen slaves. To my surprise, the young man knew a few English words. I let him in, gave him a stone pipe as a gift, some tobacco and a crate to sit on. He then signaled his slaves and said ‘The Queen sends you this for your supper, extends her greetings and asks whether you would pay her a visit.’ He added that she was very old.

The slaves came in and put the queen’s gifts in my hut. First of all, there was an immense pumpkin so heavy that a man could barely lift it. Then there was a chicken, a clay pot with rice, radish, banana, cassava, eddoes (a kind of grey root that in taste reminds me of our potatoes) and boiled maize, a dish that that is always part of my African menu.

Another black man brought a large calabash with sour palm wine. For a while I more or less conversed with the young prince – he turned out to be a grandson to the old queen, Suakoko – and we made the appointment for him to take me to the queen’s compound after sunset.

And so it happened.

Image from The African Republic of Liberia and the Belgian Congo: Based on the Observations Made and Material Collected during the Harvard African Expedition, 1926-1927

We first walked through the village covered in darkness where from all the roofs, or better still, through all the roofs, smoke was rising. Here and there a dog was barking and in the surrounding trees and on the roofs, crickets gave a deafening concert that in the forested areas in Africa accompanies nightfall and is sometimes so loud that it makes conversation impossible.

We arrived at a big palisade wall with a small gate, blocked by a heavy door made of one piece of wood. After that another door, so low that I could hardly enter it even when bending down. That door gave access to a courtyard where a herd of goats tried to run off in the darkness.

After that, we passed other obstructions and courtyards until we finally seemed to enter the space where Queen Suakoko resided. Then two squatting figures rose from the darkness without producing a sound and stopped us. The prince exchanged a couple of words with them, and I was allowed to enter.

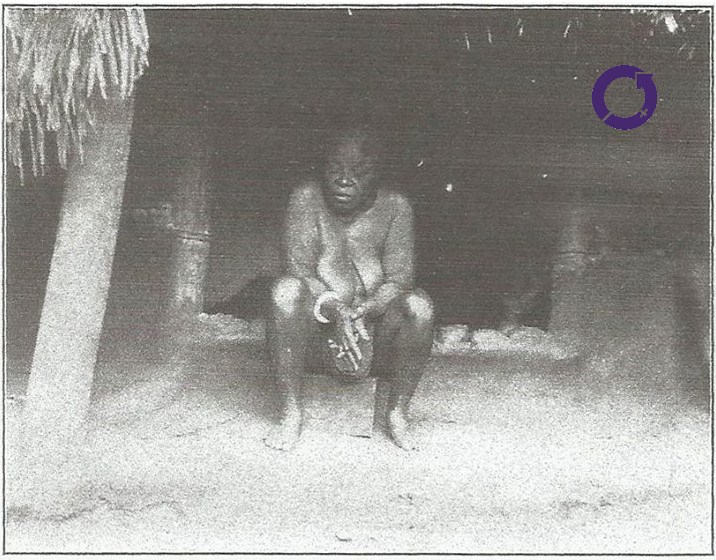

Behind this gate, a small open square within the middle a roof made of palm leaves rested on four poles in what was actually no different from a big kitchen in the interior. A fire was burning under the roof and a big piece of goat on a rattan string was roasting above it. A large amount of “Negroesâ€, all dressed in robes except for the women who from the waist up are naked, sat close to the fire since the night was chilly and it was drizzling. Close to the fire, only dressed in loin cloth the old queen Suakoko lay down on a mat. She may have been 70 years old. Upon my arrival some children started to scream, but Suakoko wasn’t moving.

The old empress, who in these days in Liberia held a very powerful position, was blind. Her grandson told her I was there. Suakoko uttered some sounds. ‘Oelele [Old lady] asks what you brought for her.’

‘Tell Suakoko that I brought a lot of tobacco’, and I asked Moses, who came with me but had to wait at the gate, to pass the packed tobacco. An approving mumbling went through the entourage around the fire.

Suakoko touched the tobacco, a much desired and expensive commodity in the interior, deemed too expensive to smoke by many who would powder it and eat it in small amounts. The tobacco was instantly divided into two parts. Suakoko put one part underneath her pillow. The other part was divided further among the entourage, which again resulted in approving mumbling.

‘Suakoko very old’ said her grandson and showed me the wrinkled skin of his grandmother. ‘Suakoko blind.’ ‘I can tell,’ I answered. ‘Oelele [Old lady] lies next to the fire all day and sleeps there too’. That message was the intro to a question because suddenly the prince said ‘Oelele [Old lady] asks whether you brought Jenever (Dutch gin).’ I saw that the queen was listening attentively and was very disappointed to hear that I was not carrying gin.

I could have added that I knew that a couple of crates of gin would have literally solved all of the problems I could have encountered in the heart of Africa, but that I didn’t feel the urge to advertise this highlight of Dutch culture, that is considered to be an utter delight within the population of the “dark†continent.

My visit didn’t last long. I was preparing to leave. ‘When you return please do not forget to bring plenty gin for Oelele’ [Old Lady], asked the prince, to very modestly add to that ‘plenty money for me’. ‘I hope to remember’. And thus, I returned to my hut, easing all the babies present that found shelter behind their mother’s back all the while.

That night I had an adventure in Suakoko that was scary to such an extent that it made me curse the moment that I decided to go to Africa without weapons. But it would take too long to share that story.

The translation was conducted by Andrea Stultiens of the Historical Preservation Society of Liberia. Images are from “The African Republic of Liberia and the Belgian Congo: Based on the Observations Made and Material Collected during the Harvard African Expedition, 1926-1927.â€