One day while I attended high school, my teacher punished me by sentencing me to kneeling in class for hours. As time went by, I began to feel intense pain in my body, triggering what is known as a crisis. I knew that if I continued in this position any longer I could collapse or even worse.

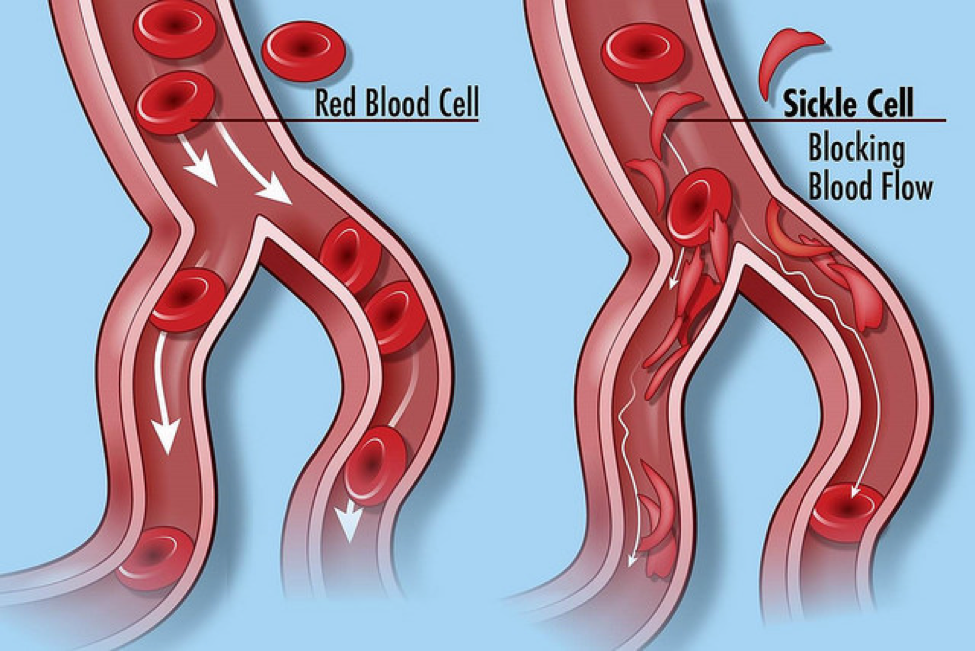

You see, I live with sickle cell disease, a painful and incurable genetic disease that is caused by abnormalities in one’s red blood cells. I haven’t always been comfortable admitting publicly that I have SCD, and even now, it’s a struggle to make this disclosure.

When I explained to my teacher what was happening, he shouted, “You know you have SCD then you like to make trouble?†After that, I received unwanted attention from curious classmates. They could not stop asking questions like, “Is it contagious?†No, it is not contagious but, it is a deadly disease that children in Liberia are not fully cognizant of, and are unfortunately killed.

That was eight years ago. Eight years later, Liberians are still blatantly ignorant of what SCD is, even though like malaria, it is one of the highest causes of deaths among children.

The last time I openly wrote about my experiences was on my 18th birthday, mainly because of the common refrain that people with SCD rarely see their 18th birthday. This is true, but the reason why those people in Liberia die before their 18th birthday has more to do with ignorance than anything else. Since September is regarded as SCD Awareness Month in the United States, I’ve chosen this opportunity to tell my story and increase awareness of the disease.

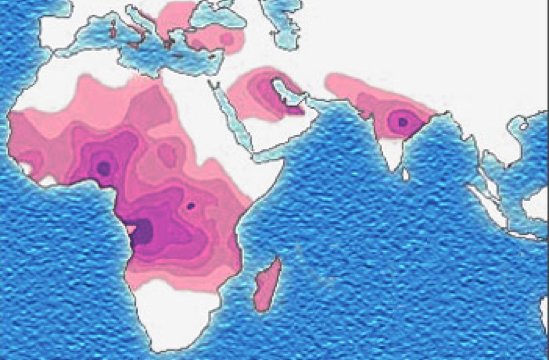

Sickle cell trait is found more frequently in persons of Middle Eastern, Indian, Mediterranean and African heritage because those geographic regions are most prone to malaria.

I don’t quite remember what led to me being diagnosed with the disease but I may have fallen sick one time and was rushed to a hospital, where the diagnosis was made. At age seven, I was subjected to this harrowing disease. Thankfully, my mom understood what having SCD meant so I owe being healthy to God first and then, her.

Growing up with SCD in Liberia was appalling. The secret behind acceptance is not only having people accept you for who you are, but also accepting yourself in full cognizance of rules you have to live up to.

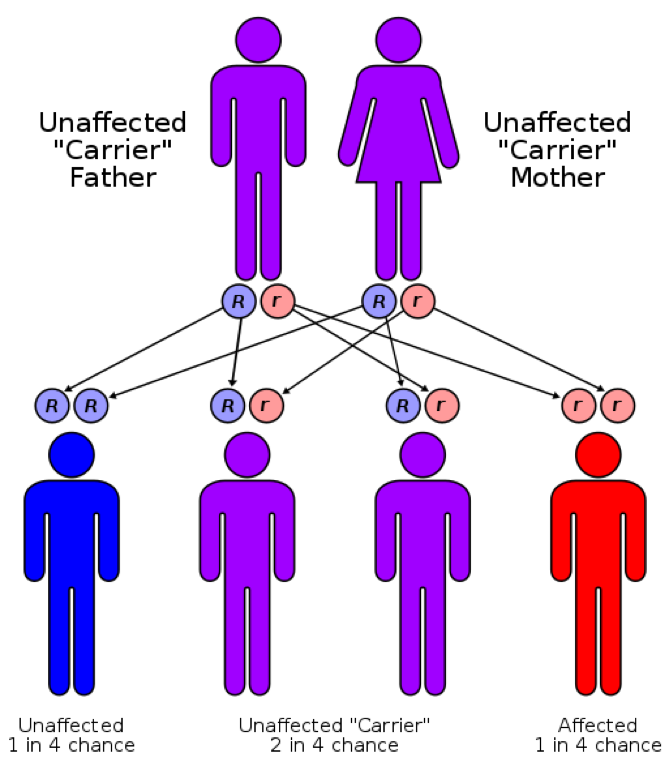

My dad loved me but he found it hard to accept that his daughter had SCD. Family members often asked, “How did Susu come to get SCD?†That question suggested that I was not his legitimate child. However, my father was not aware that he carried the sickle cell trait and while he did not have the disease and experienced no symptoms throughout his life, he could still pass on SCD to an offspring if he procreated with someone who had SCD – my mother (Read more about how the disease is passed on here).

A diagram showing how two parents, who do not have the disease but are carriers, can pass on sickle cell disease to their offspring.

My mom, who, like me, has the disease, has lived with one of the worst blood disorders.

She grew up in the 60s with SCD in a place like Lofa – rural Liberia – where barely anyone knew what SCD was. Even my mom did not know she had the disease until she was 16 years old. I was surprised she lived until the age of 16 because not every person with SCD has a long lifespan.

Mom was different from her childhood friends and because of that, they called her lazy. However, what people saw as laziness was just a manifestation of the difficulty of blood flow through her veins, because of the abnormal “sickled†shape of her red blood cells. Mom wouldn’t be able to carry a bucket of water for too long before getting tired. Mom would get sick because of malaria, which can easily kill people with SCD.

Like mom, I too did not participate in physical education classes in high school because when I tried to, I would be crippled for at least a week. My legs would get swollen because not enough blood was being transported to my bones. As a result, they were not strong enough to be stood on.

Exposure to extreme weather, whether hot or cold, causes me great pain. Additionally, I cannot drink too much alcohol or smoke; it lowers the oxygen level in my blood which causes [the] crisis. I also have to take folic acid, Vitamin D, and heavy painkillers every day for the rest of my life.

Unlike everyone else, I need supplements to help create new red blood cells. I also know many of my sickled friends who must have blood transfusions once every month to avoid severe crises.

I can’t begin to imagine how many children in Liberia with SCD die every day because they have not been diagnosed with the disease.

It was not until 2006 that the World Health Organization pronounced SCD as a top health priority in Africa, in recognition of SCD’s major contribution to infant mortality. Many children under five years of age die from SCD.

A pilot study for the screening of newborn children with SCD concluded that “an estimated 242,200 infants are born with SCD in sub-Saharan Africa annually, and the majority of those do not have access to newborn screening.†Heart-wrenchingly, many countries in Africa still do not have the facilities to screen children at birth for SCD and Liberia is not an exception.

Not being diagnosed is one thing, but living with the disease all your life and being unaware of things to avoid as SCD patients is another. Another study published about newborn screening for SCD asserts that 1,700 children are born with SCD in Liberia and 50-90 percent of them die prior to their 5th birthdays. “In 2012, a successful pilot neonatal screening program was initiated at a hospital in Monrovia. In one year, nearly 3,000 infants were screened for SCD.†This research confirmed high infant mortality rates are partly due to SCD, its lack of awareness and necessary health care.

Children with SCD can easily die from malaria. While growing up, I would often get malaria and be hospitalized for 2-3 months during the rainy season. As a result, I was only in high school for a semester of every year. Now imagine a kid with SCD who does not have the resources to be properly treated.

50-90 percent of Liberian children born with SCD die prior to their 5th birthdays. Photo: Direct Relief

Before writing this piece, I was discussing with my mom about how infrequent my crises have been over the last seven years. In fact, since I moved to the U.S. almost four years ago, I have not had any severe crises. The most recent was when I unknowingly drank a friend’s orange juice that was infused with marijuana. I ended up in the emergency room, almost having a stroke. Now, I mention this to emphasize on what the lack of awareness means for SCD patients.

When I told my mom that people at home were more likely to experience crises than I did, she concluded the difference is due to the lack of self-awareness among Liberians. I agreed with her. I am sure my experiences with less severe crises is partly because I had a mom to guide me through my adversities. Unlike those who have SCD and are not fortunate to have a mom like mine. Moreover, in the U.S., I have been blessed to have a SCD specialist, a primary care doctor, and a social worker.

I see my SCD specialist at least three times a year. In those specialized visits, I am routinely checked to ensure that the amount of oxygen being transported through my body is high. If those levels are low, it could lead to organ damage. I also get examined for the strengths of my lungs, brain, chest, heart, and bones.

Being in the U.S is a blessing for SCD patients but this is not the point that I want to stress here. Newborn screenings are provided to infants at birth and when diagnosed, they are afforded with good health care that manages their SCD from childhood to adulthood.

That is not the case in Liberia where I cannot get my hands on tangible data about SCD doctors in Liberia or initiatives carried on to create awareness about SCD in Liberia. The few awareness being conducted are done by Liberians living out of the country.

SCD should be top health priority in Liberia. Liberian health authorities should not have to wait for an outsider to notice that not having mandatory newborn screening for SCD is a serious problem. Doctors in Liberia ought to be aware of SCD crises when children are brought to the hospital and when diagnosed, the parents should be educated about their children’s health. There ought to be resources provided to children to guide them from childhood to adulthood.

Massive awareness of SCD in Liberia can ensure people that the disease is manageable. I am now 21 years old and my SCD is manageable.

Featured photo by Darryl Leja/NHGRI.